|

Coopers and Scribers, Jameson Distillery, Smithfield, Dublin City.

My paternal great-grandfather Patrick Magee stands in the back row, second from the right. |

This is an updated version of a post which first appeared in the summer of 2012 after I came upon a surprising number of sites that posed the question, 'Did you know your Irish ancestors were tenant farmers?'. 'Well no, they were not, not all of them', was my rhetorical response. This update includes new links to assist you in finding out more about those Irish ancestors who were not farmers.

While 19th century statistics show that most Irish worked the lands as tenant farmers, the plain fact is not everyone who ever lived on the island of Ireland was a farmer.

Your ancestors may have lived in an urban area such as Dublin City. The city of Dublin is over 1000 years old, a very significant period of time within which to search for ancestors who were neither farmers nor farm workers. Even some of those who lived outside the walls of the metropolis were not necessarily farmers. As well, there were some Irish who were land owners, and you may find your ancestors among them (see

Failte Romhat site).

If you are interested in statistics, including those which cover types of occupations in Ireland, dating back as far as the 1821 census, then visit the

Online Historical Population Reports Project. Here you will find all of the published population reports, including census reports, created by the Registrars-General for Ireland (as well as England, Scotland and Wales).

Although I have a fair number of farmers on my family tree, there are also quite a few for whom the scythe and the spade were foreign instruments. Consider the following professions held by some of my family members:

BALL Family:

Patrick, Francis, Patrick [the second], Anthony, Gerard: Carpenters, Box Makers & Cabinet Makers

CAVANAUGH Family:

John and William: Proprietors of a Carman's Stage.

A carman's stage was a particular type of 18th century inn, usually found on the outskirts of Irish towns, along the turn-pike system of roads in the period. It's purpose was to provide long haul car-men — those who ferried people and goods around the country — with a stopover place at which they could break their journey in order rest, and feed and water their horses, as well as themselves.

FITZPATRICK Family:

Thomas: Vintner, Victualler, Grocer, Coal labourer

Thomas Jr., called Tom: Jockey

GERAGHTY Family:

Patrick: Car-man, then Car Proprietor

A car proprietor was the owner of a business that provided all manner of horse-drawn carriages, such as flys, landau carriages, coaches, and funeral corteges in the 19th and early 20th century, and automobiles in the 20th century. As well, they provided the service of chauffeuring clients — or corpses, should that be the case — in those vehicles.

Austin: employed by the ESB: the Electricity Supply Board

George: worked for Bord na Mona: the Irish Turf Board

John: Car Driver (driver of the aforementioned 'carriages')

Michael: Parish Priest, and later Canon in the Roman Catholic Church

Patrick: University Professor

Thomas: Clerk at Guinness Brewery

KETTLE Family:

Andrew J.: Secretary of the Land League (okay, I admit it, he was a farmer too.)

Thomas: Barrister, Economics Professor at UCD, Writer, WWI Journalist, Poet, and Soldier in the Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

Laurence: Electrical Engineer: Chief Electrical Engineer for Dublin City

Patrick: Barrister and Justice of the Peace

MAGEE Family:

Patrick: Scriber and Clerk at Jameson Distillery

Michael: Scriber at Jameson Distillery, Clerk at Patterson's Match Factory,

and 2nd Lieutenant, Section Commander, A.S.U., 'A' Comp. 1st Battalion, Irish Republican Army.

Francis: Clerk, then Manager of Jameson Distillery,

and a service member of the Irish Free State Air Force detachment at Baldonnell.

WARD Family:

Thomas: Mariner

James Joseph: Master Mariner, and ultimately Captain of his own ship

Learning the occupations of your ancestors may give you insight into the fortunes of the family.

By discovering the professions held by your ancestors, you may be able to glean information about their social status, level of education, and even migration patterns of a family.

With respect to the jobs held by women: In the census records, you may find an unmarried female family member employed outside the home. Her wages would have be used to supplement those of her father and any brothers for the support of her family. You may find a widowed woman working as a char-woman, seamstress, milliner, or tailor's assistant. These kinds of jobs were often relegated to such women, barely providing them with a subsistence wage. Also, an early 20th century record which reveals a married woman with a profession may hint at a suffragette.

The male main breadwinner of the family may have held a single job long term, or may have held many jobs over time, particularly if he was an unskilled labourer or if his job entailed travel.

Unskilled labourers might have to move around the country, or to England, Scotland, Wales and beyond, in search of work. Many unskilled Irish labourers found work on the docks in Liverpool. If you think your ancestor may fit this profile and you cannot find him in the Irish census records, consider searching in the

census of England. In Liverpool, you will find a high concentration of Irish families living near the Liverpool docklands in the densely populated wards of Everton, Kirkdale, Scotland and Vauxhall. As well, many Irish found work in the Lancashire mines.

Consider the following:

1. Marriage registrations.

Civil registration of ALL birth, marriages, and deaths in Ireland began in 18641, 2, and these records are a boon for researchers because they offer so much more information than the baptismal and marriage entries in parish registers, including the professions of those mentioned on the record, such as the betrothed and their fathers.

It was not unusual for sons to follow in their father's footsteps, so you may find a son in a similar profession to that of his father. For example, in the case of my Ball family members, the craft of working wood was passed from generation to generation, with the sons and grandsons becoming cabinet makers. The marriage record of my maternal great-parents Francis Ball and Jane Early shows that continuity.

|

24 August 1884:

Francis Ball, carpenter, son of Patrick Ball, carpenter, marries Jane Early. |

*********************

While the marriage registration below for my maternal great-grandaunt Alice Fitzpatrick and her husband James Joseph Ward indicates that her father was a farmer, it also reveals that both James and his father were Mariners. Interesting to note Alice's profession is pegged as 'Farmer's daughter'.

|

11 August, 1886:

James Ward, mariner, son of Thomas Ward, mariner, marries Alice Fitzpatrick, Farmer's daughter. |

*********************

In the case of my maternal great-grandfather Thomas Fitzpatrick and his bride Mary Teresa Hynes, although both of their fathers were farmers, the record indicates that at the time of their marriage Thomas's profession was that of 'Vintner' and Mary's that of 'Shopkeeper'. Turns out, Thomas was the proprietor of a '7-day Licensed House', that is, a public house, a 'pub', authorized to sell wine and spirits.

|

20 September 1893:

Thomas Fitzpatrick, vintner, marries Mary Teresa Hynes, shopkeeper. |

*********************

2.

Birth Registrations

On the civil registration record of a birth you will find the occupation of the child's father included. If your ancestor came from a large family, compare the birth registration records of all the children, and you will get a good picture of their father's working life, giving you insight into the fortunes of the family from the changes you see in employment. Also, a comparison between the profession indicated on a marriage registration record and the birth registrations of the children born to that marriage may reveal a change in profession.

|

| In 1895 Catherine Geraghty is born to Patrick Geraghty, car man. |

|

By 1903, as noted on this birth registration of his son George,

Patrick Geraghty is a Car Proprietor, the owner of his own business. |

*********************

As I previously noted above, on his 1893 marriage registration, Thomas Fitzpatrick declared his profession as that of a 'Vintner'; however, by 1894 and the birth of his first born child Mary Angela, the record shows him as a 'Victualler and Grocer'. Seems this is a marker of a beginning trend of fortune's downward turn for Thomas, as his 1901 English census record and 1911 Irish census record will bear out.

|

| 2 September 1894: Mary Angela Fitzpatrick is born to victualler and grocer Thomas Fitzpatrick. |

*********************

3.

Cemetery registers.

Depending on the cemetery, and the time period of the record, the job title or profession of the deceased, or the father or husband of the deceased is usually listed in the register. For example, below is an image from the

registers of Glasnevin Cemetery. It is the burial record of Jane Ball, baby daughter of my maternal great-grandfather Francis Ball. You will note Jane is referred to as 'Box maker's child'.

|

Jane Ball, Box maker's child.

Extract from Glasnevin burial register of 1889.

Click on image to view larger version. |

4.

Obituaries and Newspaper Advertisements

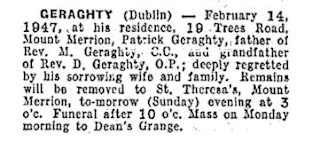

Although the professions of none of his other children are mentioned in the obituary of my paternal great-grandfather Patrick Geraghty, the profession of his son Michael and that of one of his grandsons shows up in the first line of the obituary, '... father of Rev. M. Geraghty, C.C., and grandfather of Rev. D. Geraghty, O.P.'. You may come across this in the obituaries of your own ancestors, particularly if a family member held a job considered to bear some prestige.

If you have an ancestor or family member who had an established business such as a pub, grocery, farm, etc., and then suddenly didn't, check out the auction advertisement columns in newspapers of the period.

Newspaper ads may include interesting details which might give you insight into the life of your family member. For example, auctions for the selling off of such things as a business, household goods, large numbers of livestock (for farmers), and leases on houses or plots of land may be a signal that he is about to change professions, or his family might be in trouble financially, and they may be preparing to migrate elsewhere.

In 1897 Thomas Fitzpatrick auctioned off his 7-day Licensed House. You will notice in the auction ad below, dated 5 October 1897, a reason is provided for the sale of the pub. It states, '[Thomas Fitzpatrick] finds his farm and other business requiring all his attention.'. In fact, this sale may have been precipitated by the fact that Thomas was moving on. Just over a year later Thomas and his family were living in Liverpool.

*********************

5. The

Irish Census

Irish census records from 1901 and 1911 have a column for the specific identification of the job held by an individual at the time of the census taking.

On the National Archives site you can even search by occupation.

(see NAI search page). Click on 'more search options' to search by occupation.

It is apparent from this snippet on the left from

their 1911 Census form that Thomas Michael Kettle wanted to ensure his profession was well understood, as well as that of his wife, Mary Sheehy. In addition to Thomas Kettle's occupation as a Barrister and Economics professor, both he and his wife Mary are recorded as graduates of the National University of Ireland, and as writers.

For Thomas Fitzpatrick — once a vintner, victualler and grocer — it appears that with the move to Liverpool his fortunes greatly faltered, as the

1911 Irish census of the Fitzpatrick household finds them back in Ireland with Thomas employed as a coal labourer.

3

*********************

6.

Directories

City and Country directories are a great resource for learning about an ancestor's occupation, and some directories are freely available online (click on the blue links below to view various editions). Many of these can be found on Google Books, although not all years are available.

Some classes of workers are excluded from directories. For example you will not find landless labourers, small lot tenant farmers, and servants; however, you will find the following included: shop keepers, apothecaries, pawnbrokers, bankers, ecclesiastics, and a whole host of others.

Look for the following titles:

1751-1837: Wilson's Directory and

The Treble Almanack (Wilson's Directory was published as part of the Treble Almanack beginning in 1837).

from 1820: Pigot & Slater's countrywide directories;

Slater's Directory.

1834-1849: Pettigrew and Oulton's Dublin Almanac and General Register of Ireland

1844-present day:

Thom's Irish Almanac and Official Directory

*********************

Footnotes and Resources:

1. 1845 was the first year in which marriages (i.e. non-Roman Catholic marriages) were registered in Ireland. In 1863, legislation known as the ‘Registration of Births and Deaths Act of 1863’ established the legal requirement that the births and deaths of

ALL Irish born persons be registered with the government. The act was amended on 28 July 1863, via a private member's bill in Parliament, to include all marriages as well. The civil registration of all of these life events officially began on 1 January 1864.

2. For the 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland you can order copies of civil registration records online via the website Certificates.ie at

http://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/1/bdm/Certificates/. This site does not offer a search option, so you must have in hand the details of the record you want. See

this link for details about the information required, and

this link for full details with respect to exactly which records can be applied for online.

For the 6 counties of Northern Ireland, you can search for and order copies of civil registration records online via the website of GRONI, the General Registration Office of Northern Ireland at

https://geni.nidirect.gov.uk.

Indexes for Irish civil registration are available on FamilySearch.org at

https://familysearch.org/search/collection/1408347.

3. The Fitzpatrick family moved to Liverpool sometime in late 1898 or early 1899, and the family did not fare well there (See

'Probably General Debility': The death of Little Joseph Fitzpatrick, aged 6). The 1901 Census of England reveals that Thomas and his family were living in the docklands of Liverpool, and he was working as a casual labourer on the docks.

©irisheyesjg2015.